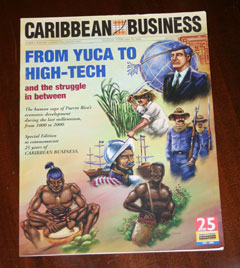

From Yuca to High Tech

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

To mark its 25th anniversary in 2000, the Puerto Rico newsweekly Caribbean Business hired me to produce a different kind of history of the past thousand years, focusing on the economy of the island and how people earned a living over the centuries. While certainly not a comprehensive history, the resulting 30,000-word publication, which I wrote entirely, provides snapshots of Puerto Rico's development at selected moments in time.

- 1000: The Taíno civilization begins to flourish

- 1500: European conquest

- 1600: British for a while and other battles

- 1700: The age of pirates and privateers

- 1800: A dormant colony awakens

- 1900: Rough start with the U.S.

- 1910: The dawn of King Sugar

- 1920: The new regime — the Jones Act

- 1930: Desperate years

- 1940: Bread, land and liberty

- 1950: The turning point

- 1960: Turning toward modernity

- 1970: A new Puerto Rico

- 1975-2000: An economy matures

1600

British for a while and other battles

Imagine a Puerto Rico of today in which everyone spoke English (not American style, but the Queen's) and drove on the left side of the road. The name probably wouldn't be Puerto Rico, local athletes would be key members of the West Indies cricket team, and whatever political status would prevail, nobody would be talking about joining the United States.But for a few germs, it might have happened that way.

While Spain's colonial outpost on Puerto Rico came under attack from the French and the Dutch, as well as being harried by privateers, the Spanish never surrendered to any attackers except the British.

Spain had spent the second half of its first century in Puerto Rico building defenses. Ponce de León's settlement in Caparra had been moved to the present-day site of Old San Juan, and by the end of the 1500s it was protected by several fortifications, including a smaller version of today's El Morro guarding the mouth of the bay.

Attacks were a constant worry. In 1595, Sir Francis Drake decided to take on the formidable challenge of attacking San Juan. On the ramparts of El Morro, 27 cannons waited to welcome the Englishmen, and more cannons and soldiers were posted at Escambrón, the mouth of the Rio Bayamón and other strategic points.

Attacking at night, the English set afire the Spanish ship Magdalena, but that proved to be their undoing. The fire lit up the scene of the battle, helping the soldiers to aim their weapons at the invaders. Some 400 English troops died, compared to 40 Spaniards, and Drake sailed away in defeat.

Queen Elizabeth wanted Puerto Rico, however, and almost immediately sent a new expedition led by the third Earl of Cumberland, Sir George Clifford. With 20 ships and a thousand men, Cumberland avoided the tactics tried by Drake and decided to attack San Juan by land.

His first attempt to enter through what is now Miramar was repelled, but another landing near Escambrón was successful, and the English troops marched into the city.

Some residents had fled inland and the soldiers and government officials had taken refuge in El Morro. Cumberland set about sacking the town and laying siege to the fortress. After 15 days huddled inside El Morro, short of food and ammunition and constantly bombarded, Spanish governor Antonio Mosquera surrended. For the first time under Spanish colonial rule, a foreign flag was raised over Puerto Rico.

But the island remained under Cumberland's control for just 65 days. In the countryside, locals harassed the invaders, but the real threat was too small to be seen. An epidemic that had already passed among the islanders now laid waste to Cumberland's troops. Cumberland had ordered his chaplain, the Rev. John Layfield, to keep an account of the invasion. Layfield described the disease in his diary.

"The illness is a diarrhea, which changes in a few days into a flow of blood," Layfield wrote. Victims suffered intermittent fevers and within days lost their strength. When their arms and legs felt cold to the touch, "that was taken as a sign that death was near."

Cumberland had lost 200 men in battle while taking the capital, but the epidemic killed 400. With barely enough troops to crew his ships, much less maintain control of the prize he had seized from Spain, Cumberland finally fled the island, but not before he burned the houses of San Juan, destroyed crops, stole the organ and bells from the cathedral and took booty ranging from 2,000 slaves to a marble windowsill that caught his eye.

Twenty-seven years later, the Dutch would briefly take San Juan, and would once again burn it to the ground when they found they could not hold it in the face of a shrewd Spanish counterattack that featured nighttime raids against the invaders in which as many as 50 Dutch throats were slit before dawn. But in a century of warfare among the European powers, only the Earl of Cumberland was ever able to say that Puerto Rico had surrendered to him.

Moments that changed the course of history can be found in many places, and not all the actors are great men and women. Some are as small as a bacterium that ensured that Puerto Rico remained a colony of Spain and not another part of the British empire.

§§§

A walk in San Juan at the dawn of the 17th century was nothing like today. The problem then was a lack of population, not crowding. Spain was constantly concerned that it did not have enough loyal subjects in Puerto Rico to keep the island from foreign control.

Puerto Rican, not Spanish

In the early years of Spanish settlement of Puerto Rico, the residents of the outpost were a small band of whites supported by a larger number of black slaves and Taínos. They came from Spain to this new home, but they clearly believed themselves to be Spanish.

When did the whites of Puerto Rico begin to think of themselves as belonging to Puerto Rico, not to Spain? Feelings of nationalism have ebbed and flowed over the centuries on the island. When were the first seeds planted? When did Puerto Ricans begin thinking differently from Spaniards?

Historians can point to a couple of documents from the mid-1600s that lay untapped in archives in Spain until centuries later.

One was written in 1644 by Damian López de Haro, who was sent to Puerto Rico to be bishop of San Juan, an appointment that did not thrill him. In a letter, he described Puerto Rico as "a very small island, lacking in supplies and money."

López de Haro wrote that the men were smugglers, the women lacked class, it was too hot and the only thing good about the place was that there was a bit of breeze.

(By one account, López de Haro would die three years later in a plague that killed 500 people.)

A few years after López de Haro wrote his letter, Diego de Torres Vargas, who was born in Puerto Rico, took a very different view in a history of Puerto Rico he wrote for a volume to be published in Madrid.

After detailing the events of the young colony's history, he recounts the accomplishments of los naturales, as native-born islanders were called. He probably never read López de Haro's comments, but it was as if he were responding to them.

"The women are the most beautiful in all the Indies, honest, virtuous and hard-working," he wrote, leading "prudent men" to come to the island in search of wives. The men were mostly tall, he described, with lively minds. They were active and brave.

What's more telling is that de Torres Vargas used the word patria in reference to Puerto Rico when he was talking about los naturales. They were Puerto Ricans, in that sense, not Spaniards.

López de Haro, Spaniard. De Torres Vargas, Puerto Rican. It would not be the last time Puerto Ricans and their colonial rulers would not see eye-to-eye.

It was, however, one of the first, and a sign that a new society was forming in Spain's distant outpost.

San Juan consisted of about 200 houses in the years just before Cumberland set fire to most of them. The homes were spaced apart and an abundance of trees gave the city a country feel. Not only were the streets unpaved, but they were so sparingly used that grass grew on them, providing snacks for the beasts of burden used by the residents.

There was no room for agriculture in San Juan, and the capital relied on the farms on the main island for its food supply. In the early years of the 1600s, the cathedral had been repaired but still didn't have a bell to replace the one Cumberland stole. The city did have two hospitals.

If San Juan was something less than thriving, the other fragile settlements were in worse shape. San Germán couldn't muster enough money to build a stone church, and San Blas de Illescas de Coamo was so poor it couldn't support its priest, leading the bishop to ask in 1618 for financial help from the crown.

Those were the only three settlements on the island, though about 30 families had gathered together in the area that is now Arecibo, and in 1616 it was named San Felipe de Arecibo.

While the ruling class lived a life of privilege in San Juan, the mass of the population toiled at survival. Slaves provided most of the labor on the farms outside the city. Sugar production was minimal because of the multiple scarcities: lack of local demand, lack of labor, lack of capital for improving processing, and the diminished market in Spain.

Cattle farming grew quickly. The owners were more concerned with the hides, which fetched a good price in Europe, than with the meat. Ginger became the most important crop, as it required less work. In 1608, Spain outlawed the growing of tobacco on Puerto Rico, probably to protect the industry in Cuba.

Worst of all for Puerto Rico, the island was only allowed to do business with Seville in Spain, and wasn't even allowed to trade with other Spanish possessions in the Caribbean.

The people of Puerto Rico, neither for the first time nor the last, found themselves in a vice, squeezed by Spain's severe restrictions on trade, the onerous taxes imposed by the local officials and the constant threat of attack by Spain's European rivals.

"As a consequence of the extreme poverty, the Puerto Rican people, in a moment of desperation, decided to evade the unjust laws that oppressed them," wrote Gilberto R. Cabrera in "Puerto Rico and its Intimate History," a two-volume history of the island.

"Due to the isolation, the economic situation and commercial abandonment, smuggling became the most important way to survive," Cabrera wrote.

Illegal trade was virtually a necessary way of life for the outlying settlements, but it even took place under the noses of the Spanish governors in San Juan.

One account tells of how after the walls around the city were completed in 1638, smugglers would go to the wall facing the bay and lower goods for illegal export to the waiting ships, then raise up the goods being smuggled in. Cabrera says that even government officials promoted the smuggling and took their cut, of course, especially in the second half of the century.

§§§

The end of Spain's first century in Puerto Rico saw the rise not only of smuggling, which remains an important issue in the Caribbean 400 years later, but also the beginning of another situation that is still debated in Puerto Rico today. It's called federal transfer payments today, but back then it was called the situado.

Early on, it became clear Puerto Rico could not support itself, especially as ever-larger numbers of troops and fortifications were required for defense. Puerto Rico did not have New Spain's (Mexico's) gold nor Peru's silver.

The situation was often desperate. On one occasion, the governor in charge of the troops in San Germán sold his uniform to raise money to buy food for his soldiers. Money was always short. The colonial administrators levied taxes on land and slaves and a 2 percent sales tax; took a cut from trading activity; and even received a portion of the tithes to the church, but still could not make ends meet.

In 1582, Spain approved the situado, a payment to be received from Mexico annually. But the first payment didn't arrive until five years later; a pattern that was to be repeated often. Many times, the situado arrived years late and as pirates and privateers increasingly became a scourge in the Caribbean, it was often looted before it reached Puerto Rico.

Soldiers sometimes went months without pay, and when local money dried up, paper notes were issued that could be redeemed when the metal coins finally arrived from Mexico.

Puerto Rico became totally dependent on this subsidy to maintain the military defenses on the island. By 1620, the situado had reached 645,290 reales, the Spanish currency at the time, and accounted for 85 percent of the colony's income, a dependence that would last, in varying degrees, for more than two centuries.

Transfer payments, smuggling, poverty, evasion, the island's use as a military post for a major power...

Sounds familiar?